by Dirk Townsend – Part 1 (check back for part 2, coming soon)

Boni was driven by love and caring for the people, plants and animals around her. She was inquisitive and well-read on politics, food, agriculture and dozens of other subjects. She was constantly applying her knowledge to care for her surroundings. She felt the pain of the world and wanted to fix it. She was ahead of her time in so many ways. She was brave, selfless and determined.

Her caring for the planet led her to begin recycling in the 60s when it was a struggle to find anyone who even knew how to recycle our plastic, glass and newspaper. I remember bundling everything up and then storing it for months before it was worth the long drive to what might have been the only recycling depot on the west coast.

She was an environmental activist. I remember when I was 2 or 3 years old asking her why she couldn’t put me to bed some nights and she telling me, “I am going to fight pollution”. At that age, I imagined her kicking and punching pollution to the ground, and since my mother could do anything, I fully believed that was what she was doing those evenings. However, she was actually attending meetings as an early member (maybe a founding member?) of SPECS, Scientific Pollution and Environmental Control Society, whose members had a foundational impact on Canadian environmental groups and cross-pollinated to form an off-shoot named, “Greenpeace” a few years later.

The arrival of twins (Jill & Chad) in 1968 three years after I was born, in combination with her evolving separation/divorce through 1969 and her purchase of her farm near Chilliwack, BC focused her attention towards raising healthy, strong, independent children, as well as, towards the land itself that she found herself living on.

Education became a topic when she sent me off to Kindergarten at a local school. Not impressed with the educational philosophy at Watson Elementary in 1969, she became driven to find an education for her children that was more in alignment with her values. She found the John Dewey inspired, Vancouver New School which was “informal, unregimented, non-competitive, non-conformist and encouraged growth in self-discipline, self-reliance, and independence” (ref. Alternative Schools in British Columbia, 578 pages; the New School’s Conception and Ideology begins on page 23). I attended that school for the next three years and remember being able to wander at will and interact as I pleased, though always with an array of projects and learning materials at the ready. However, it became too much to drive into Vancouver several times a week (I stayed with friends many weeknights), especially with the added logistical difficulties of Jill and Stripes’ becoming of school age. Also, the New School had it’s own internal issues as it charted it’s pioneering course.

Thereafter, Boni researched and interviewed local teachers from the surrounding schools and hand-picked what she hoped would be more open-minded educators, though with mixed success. This was a hard period for her since few people in socially conservative Sardis understood or cooperated with her priorities. Around the same time she also tried to pursue her career as a registered nurse in Chilliwack, but was taken aback by the traditional, authoritarian and judgemental attitudes she encountered. She was used to working on the vanguard of child-centred care philosophy at Sickkids in Toronto (ref. Sickkids history) and decided her local experience paled in comparison and gave up nursing in Chilliwack after a brief period.

She knew this social environment would have an impact on her kids and alternately steeled us, consoled us and intervened to help us through some difficult experiences. The ‘Lord’s Prayer’ as well as spanking and strapping were still elements as were some odd experiences with teachers. I remember waiting outside the classroom in the hall for hours as the class rehearsed for the school production of “Joseph and his Technicolour Dreamcoat” to which Boni objected due to its religious content. I remember being picked (By Mr. Huth to prove my discipline, I suppose) to ring the school bell for an entire school year having to run in early and on time 6 times a day even though the principal and administrators were always sitting in the office right beside the bell switch. Not to mention the hazards of getting to school on our bikes: past the kids who waited for the Timothy Christian School bus and had nothing better to do than scream that we were sinners and would go to hell and then attack our bike tires with their axe; or a little further along the route where we had to survive intermittent pursuit by the native reserve kids who were looking for someone to beat-up.

I don’t know the details of what insults Boni herself must have suffered as she didn’t share this, but the experience of being discounted and judged as a crazy, husband-less mother of three with a large unkempt herb garden hurt Boni and made her wary of participating in Chilliwack society. Nevertheless, she was not dissuaded from any of her causes and carried on making friends and alliances where she could and focusing her energies on her passions.

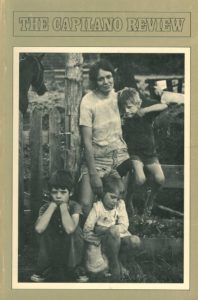

Boni, Dirk, Jill & Chad – Cover of Capilano Review – Fall 1975

Boni, Dirk, Jill & Chad – Cover of Capilano Review – Fall 1975

Boni took food seriously; where it came from, how it was grown, how healthy it was, the wider societal effects, etc. Food was intertwined with her children’s health, her own health, her animals, her farm, her politics and her livelihood, in short almost everything she cared about. Her philosophy on food developed in stages. I remember travelling with her to pick-up our health food order at the CRS Workers’ Cooperative (ref: CRS Case Study, page 13 also this book review) which was in East Vancouver housed in just about the scariest building my 7 year old mind could imagine (I think they got cheap rent on a previously abandoned, possibly condemned, stained and dripping concrete block industrial building). We ordered 40-pound sacks of rice or lentils, case-lots of Lifestream bread, massive vats of peanut-butter and many other bulk staple foods. We had food co-op meetings to combine our order with others. I would pour over the co-op catalogues with great delight together with my siblings to suggest foods to order. While Boni supported co-operative organizations on a political level and patronised them when she could, the direction of her own livelihood was so deeply felt that she couldn’t share control with others.

From first moving to the farm in 1969, she gradually built up the capacity to grow her own food. She embarked on a variety of experiments with keeping animals including: goats, pigs, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese, a horse, dogs and cats. I remember the tears as the pigs and chickens went off to slaughter and I remember the meat coming back in packages which nobody was keen to eat. Around 1972, with three children under 7 years old to feed, she became a vegetarian. She turned her cooking upside down to get the requisite protein and nutrients, researching and learning on the go. The goats and the chickens stuck with us for many years after; goats for milk and chickens for eggs. It became my morning job to milk the goats and if there was a lot of it, Boni would make yoghurt in mason jars kept warm in the bathtub.

She appreciated fine food, but her style was usually more austere. The food would be healthy, simple, politically correct, from the garden wherever possible, always from scratch and sometimes including ingredients from other market vendors. She had her kids cooking from a young age. I remember needing a box to stand on to get up high enough to stir the pots. Soon enough she had a schedule with each kid cooking 2 suppers a week and of course getting our own breakfast and making our own lunches. Most suppers involved a trip around the farm to pick salad herbs, vegetables and fruit or berries before these were combined with whatever else we had on hand. Cooking was mainly free-style, though occasionally a recipe was consulted, especially for baking. Often on the weekend Boni would cook a massive pot of beans, rice or sometimes a fish which we could re-purpose for our supper making responsibilities.

As she began to grow more and more vegetables and herbs she decided to build a geodesic wood-frame green-house. After Expo 67 and with the Bloedel conservatory having opened in Vancouver in 1969 we built our own just a few years later (ref: something like this). It worked very well, but turned out to be a little small and it’s 1×3 wood frame was subject to rot. A couple of years later, she researched and helped design and build another, much larger greenhouse with heat-sink capabilities that stabilised night-time temperatures through the use of stored water and heat trapping stone. She took an electrical course and a plumbing course when I was about 11 and brought back the text-books. She and I wired the greenhouses for heating pads and watering systems. A few years after this, she got a loan and had a couple of more standard hoop greenhouses put up and adding a few more over the years until she had a total of 9 operating at one time. It wasn’t uncommon for us to make an emergency expedition late on a stormy winter night with tape and staple guns to repair some loose corner.

< End of Part 1>

Thank you so much for this moving tribute to your mother and family life Dirk. Boni was a great, if somewhat quirky and often feisty, mover and shaker in so many ways. Several of the herbs on our farm, are especially the lemon verbena and bee balm, are direct descendants of her green thumb and counsel. The wee tussy mussies from her market stall brought joy and beauty to challenging days.

What a privilege to have known Boni these many years at trout lake market. I will miss our many conversations .